Patient capital investment review: one mis-step?

Patient capital is defined as investments that investors expect to hold for a minimum of 3-5 years and possibly up to 15 years depending of the characteristics of the sector.

The UK Government launched a review of Patient Capital earlier in 2017. The Review recently published a consultation document seeking evidence across a range of areas.

Evidence supports the notion that the supply of patient capital in the UK is scarce relative to the USA. Analysis within the recent consultation document suggests that UK venture capital investment would have to double – from £4bn per year to £8bn a year – to match the supply available in the US.

The policy interest in ensuring ambitious businesses can access capital sufficient to execute their growth plans appears well founded. Although growing to scale can be challenging, businesses that are able to have a transformational impact on economic performance - 0.5% of businesses registered in 1998 created 40% of the jobs created by that cohort of businesses over the subsequent fifteen years.

Length of time before exit

The consultation draws attention to analysis that demonstrates growing UK privately-owned businesses ‘exit’ earlier than those in the US.

Whether measured by the time at which they list on an exchange, through an initial public offering (IPO), or executing a trade sale, UK businesses go through fewer funding rounds than their US counterparts.

The supposition within the consultation is that this is evidence of UK businesses exiting before they reach scale, which is damaging to the businesses themselves and to the UK economy.

The inference is that UK firms would benefit from spending longer in private ownership:

“UK firms are on average less developed and have scaled up less on average when they come to major decision points about their ownership structure to support their future plans for growth. This in turn may reduce these firms’ ability to grow to their full potential by limiting their options on future ownership structures.” pp 12

International perspective

It can't be denied that this is all a little puzzling - not least because the US Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC’s) Investor Advisory Committee has recently considered evidence suggesting that the longer incubation time before IPO – stimulated by the ready availability of private capital – is damaging public exchanges.

There is a danger that a variation in the structure of capital financing that is beginning to cause concern in the US is advocated as a desirable development in the UK.

One of the principal concerns in the US is that a combination of delisting and delaying IPOs leaves main indices populated by slightly moribund large corporations that will damage market confidence.

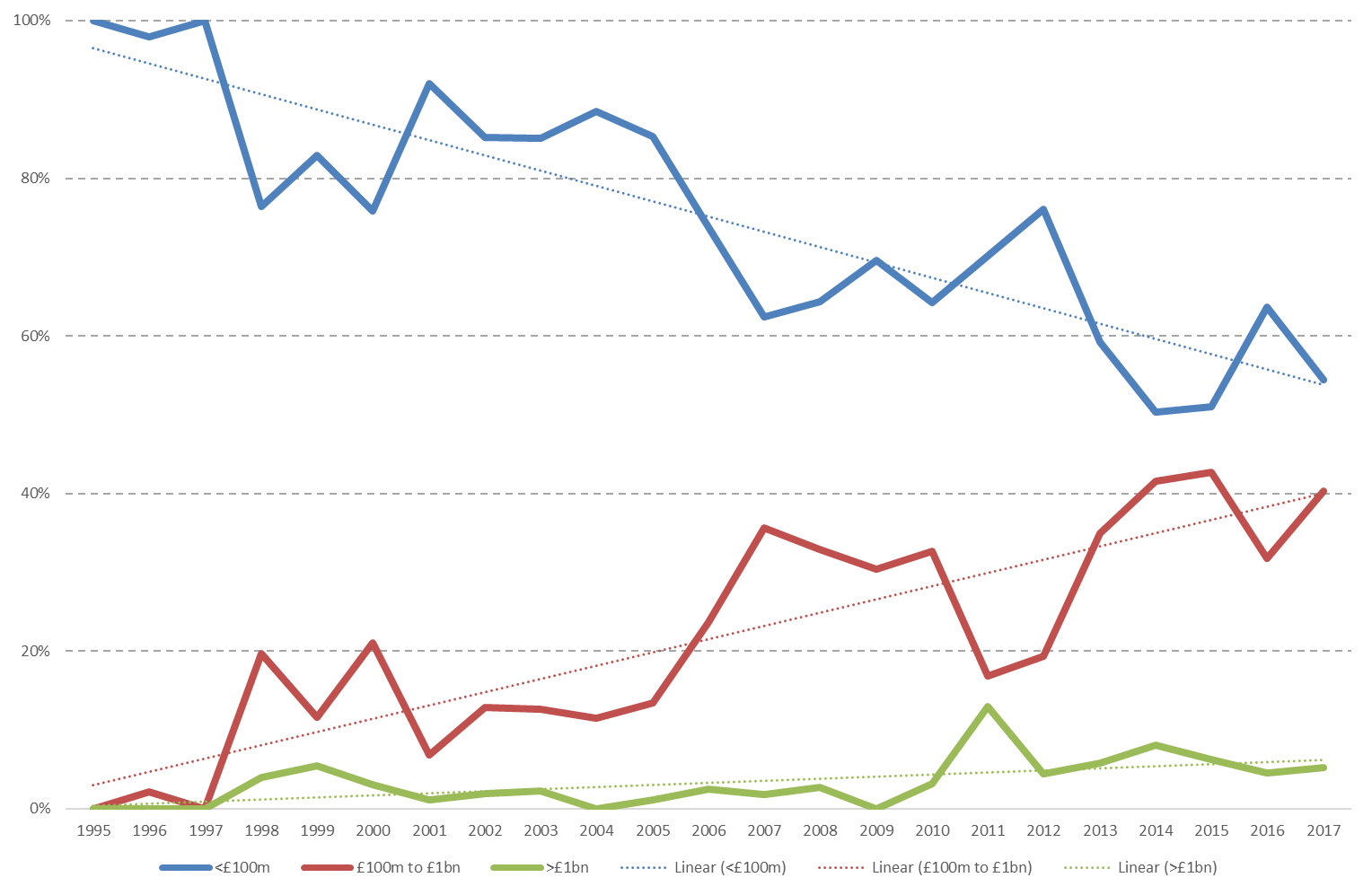

However, time series analysis of London Stock Exchange data presented in the chart below suggests the proportion of IPOs on the London Stock Exchange raising less than £100m has fallen since 1995.

This conflicts with the notion that too many UK businesses continue to exit too soon.

Source: GrowthFunders analysis of LSE data

This analysis suggests that a fundamental supposition within the consultation remains unproven. The proportion of IPOs that raise less than £100m is already falling and evidence that that remaining unlisted will benefit business growth is far from conclusive; the rationale for stimulating this through public policy is weak.

How might investors respond?

The UK Government offers investors a range of incentives to invest in early-stage companies. These incentives gradually become less generous as companies become more established; comparing the SEIS with the EIS is a good example.

Venture Capital Trusts (VCTs) offer investors an opportunity to continue to benefit from incentives while investing in companies that have undertaken an IPO and are listed (included a limited proportion on the main indices).

If the UK Government felt that the economy would benefit from companies undertaking more private funding rounds before an IPO, it could seek either to relax existing initiatives so that the tax relief that they offer can be enjoyed for longer, or introduce a new initiative targeted directly at encouraging companies to reach scale before listing.

The evidence for this appears inconclusive - the UK Government may wish to conduct its own tax efficient review before introducing such an initiative.

%20(3)%20(2).jpg)